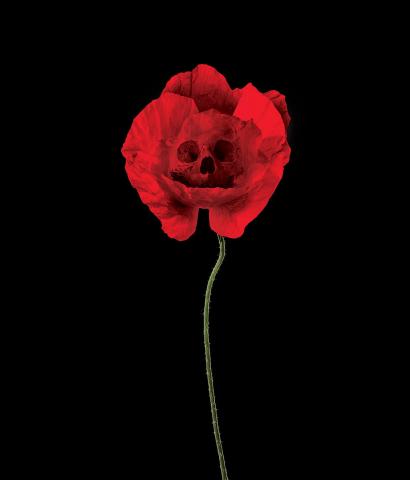

The Poison We Pick

This nation pioneered modern life. Now epic numbers of Americans are killing themselves with opioids to escape it.

By Andrew Sullivan for New York Magazine

It is a beautiful, hardy flower, Papaver somniferum, a poppy that grows up to four feet in height and arrives in a multitude of colors. It thrives in temperate climates, needs no fertilizer, attracts few pests, and is as tough as many weeds. The blooms last only a few days and then the petals fall, revealing a matte, greenish-gray pod fringed with flutes. The seeds are nutritious and have no psychotropic effects. No one knows when the first curious human learned to crush this bulblike pod and mix it with water, creating a substance that has an oddly calming and euphoric effect on the human brain. Nor do we know who first found out that if you cut the pod with a small knife, capture its milky sap, and leave that to harden in the air, you’ll get a smokable nugget that provides an even more intense experience. We do know, from Neolithic ruins in Europe, that the cultivation of this plant goes back as far as 6,000 years, probably farther. Homer called it a “wondrous substance.” Those who consumed it, he marveled, “did not shed a tear all day long, even if their mother or father had died, even if a brother or beloved son was killed before their own eyes.” For millennia, it has salved pain, suspended grief, and seduced humans with its intimations of the divine. It was a medicine before there was such a thing as medicine. Every attempt to banish it, destroy it, or prohibit it has failed.

The poppy’s power, in fact, is greater than ever. The molecules derived from it have effectively conquered contemporary America. Opium, heroin, morphine, and a universe of synthetic opioids, including the superpowerful painkiller fentanyl, are its proliferating offspring. More than 2 million Americans are now hooked on some kind of opioid, and drug overdoses — from heroin and fentanyl in particular — claimed more American lives last year than were lost in the entire Vietnam War. Overdose deaths are higher than in the peak year of AIDS and far higher than fatalities from car crashes. The poppy, through its many offshoots, has now been responsible for a decline in life spans in America for two years in a row, a decline that isn’t happening in any other developed nation. According to the best estimates, opioids will kill another 52,000 Americans this year alone — and up to half a million in the next decade.

We look at this number and have become almost numb to it. But of all the many social indicators flashing red in contemporary America, this is surely the brightest. Most of the ways we come to terms with this wave of mass death — by casting the pharmaceutical companies as the villains, or doctors as enablers, or blaming the Obama or Trump administrations or our policies of drug prohibition or our own collapse in morality and self-control or the economic stress the country is enduring — miss a deeper American story. It is a story of pain and the search for an end to it. It is a story of how the most ancient painkiller known to humanity has emerged to numb the agonies of the world’s most highly evolved liberal democracy. Just as LSD helps explain the 1960s, cocaine the 1980s, and crack the 1990s, so opium defines this new era. I say era, because this trend will, in all probability, last a very long time. The scale and darkness of this phenomenon is a sign of a civilization in a more acute crisis than we knew, a nation overwhelmed by a warp-speed, postindustrial world, a culture yearning to give up, indifferent to life and death, enraptured by withdrawal and nothingness. America, having pioneered the modern way of life, is now in the midst of trying to escape it.

How does an opioid make you feel? We tend to avoid this subject in discussing recreational drugs, because no one wants to encourage experimentation, let alone addiction. And it’s easy to believe that weak people take drugs for inexplicable, reckless, or simply immoral reasons. What few are prepared to acknowledge in public is that drugs alter consciousness in specific and distinct ways that seem to make people at least temporarily happy, even if the consequences can be dire. Fewer still are willing to concede that there is a significant difference between these various forms of drug-induced “happiness” — that the draw of crack, say, is vastly different than that of heroin. But unless you understand what users get out of an illicit substance, it’s impossible to understand its appeal, or why an epidemic takes off, or what purpose it is serving in so many people’s lives. And it is significant, it seems to me, that the drugs now conquering America are downers: They are not the means to engage in life more vividly but to seek a respite from its ordeals.

The alkaloids that opioids contain have a large effect on the human brain because they tap into our natural “mu-opioid” receptors. The oxytocin we experience from love or friendship or orgasm is chemically replicated by the molecules derived from the poppy plant. It’s a shortcut — and an instant intensification — of the happiness we might ordinarily experience in a good and fruitful communal life. It ends not just physical pain but psychological, emotional, even existential pain. And it can easily become a lifelong entanglement for anyone it seduces, a love affair in which the passion is more powerful than even the fear of extinction.

Perhaps the best descriptions of the poppy’s appeal come to us from the gifted writers who have embraced and struggled with it. Many of the Romantic luminaries of the early-19th century — including the poets Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, Keats, and Baudelaire, and the novelist Walter Scott — were as infused with opium as the late Beatles were with LSD. And the earliest and in many ways most poignant account of what opium and its derivatives feel like is provided by the classic memoir Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, published in 1821 by the writer Thomas De Quincey.

De Quincey suffered trauma in childhood, losing his sister when he was 6 and his father a year later. Throughout his life, he experienced bouts of acute stomach pain, as well as obvious depression, and at the age of 19 he endured 20 consecutive days of what he called “excruciating rheumatic pains of the head and face.” As his pain drove him mad, he finally went into an apothecary and bought some opium (which was legal at the time, as it was across the West until the war on drugs began a century ago).

An hour after he took it, his physical pain had vanished. But he was no longer even occupied by such mundane concerns. Instead, he was overwhelmed with what he called the “abyss of divine enjoyment” that overcame him: “What an upheaving from its lowest depths, of the inner spirit! … here was the secret of happiness, about which philosophers had disputed for many ages.” The sensation from opium was steadier than alcohol, he reported, and calmer. “I stood at a distance, and aloof from the uproar of life,” he wrote. “Here were the hopes which blossom in the paths of life, reconciled with the peace which is in the grave.” A century later, the French writer Jean Cocteau described the experience in similar ways: “Opium remains unique and the euphoria it induces superior to health. I owe it my perfect hours.”

The metaphors used are often of lightness, of floating: “Rising even as it falls, a feather,” as William Brewer, America’s poet laureate of the opioid crisis, describes it. “And then, within a fog that knows what I’m going to do, before I do — weightlessness.” Unlike cannabis, opium does not make you want to share your experience with others, or make you giggly or hungry or paranoid. It seduces you into solitude and serenity and provokes a profound indifference to food. Unlike cocaine or crack or meth, it doesn’t rev you up or boost your sex drive. It makes you drowsy — somniferum means “sleep-inducing” — and lays waste to the libido. Once the high hits, your head begins to nod and your eyelids close.

When we see the addicted stumbling around like drunk ghosts, or collapsed on sidewalks or in restrooms, their faces pale, their skin riddled with infection, their eyes dead to the world, we often see only misery. What we do not see is what they see: In those moments, they feel beyond gravity, entranced away from pain and sadness. In the addict’s eyes, it is those who are sober who are asleep. That is why the police and EMS workers who rescue those slipping toward death by administering blasts of naloxone — a powerful antidote, without which death rates would be even higher — are almost never thanked. They are hated. They ruined the high. And some part of being free from all pain makes you indifferent to death itself. Death is, after all, the greatest of existential pains. “Everything one achieves in life, even love, occurs in an express train racing toward death,” Cocteau observed. “To smoke opium is to get out of the train while it is still moving. It is to concern oneself with something other than life or death.”

This terrifyingly dark side of the poppy reveals itself the moment one tries to break free. The withdrawal from opioids is unlike any other. The waking nightmares, hideous stomach cramps, fevers, and psychic agony last for weeks, until the body chemically cleanses itself. “A silence,” Cocteau wrote, “equivalent to the crying of thousands of children whose mothers do not return to give them the breast.” Among the symptoms: an involuntary and constant agitation of the legs (whence the term “kicking the habit”). The addict becomes ashamed as his life disintegrates. He wants to quit, but, as De Quincey put it, he lies instead “under the weight of incubus and nightmare … he would lay down his life if he might get up and walk; but he is powerless as an infant, and cannot even attempt to rise.”

The poppy’s paradox is a profoundly human one: If you want to bring Heaven to Earth, you must also bring Hell. In the words of Lenny Bruce, “I’ll die young, but it’s like kissing God.”

No other developed country is as devoted to the poppy as America. We consume 99 percent of the world’s hydrocodone and 81 percent of its oxycodone. We use an estimated 30 times more opioids than is medically necessary for a population our size. And this love affair has been with us from the start. The drug was ubiquitous among both the British and American forces in the War of Independence as an indispensable medicine for the pain of battlefield injuries. Thomas Jefferson planted poppies at Monticello, and they became part of the place’s legend (until the DEA raided his garden in 1987 and tore them out of the ground). Benjamin Franklin was reputed to be an addict in later life, as many were at the time. William Wilberforce, the evangelical who abolished the British slave trade, was a daily enthusiast. As Martin Booth explains in his classic history of the drug, poppies proliferated in America, and the use of opioids in over-the-counter drugs was commonplace. A wide range of household remedies were based on the poppy’s fruit; among the most popular was an elixir called laudanum — the word literally means “praiseworthy” — which took off in England as early as the 17th century.

Mixed with wine or licorice, or anything else to disguise the bitter taste, opiates were for much of the 19th century the primary treatment for diarrhea or any physical pain. Mothers gave them to squalling infants as a “soothing syrup.” A huge boom was kick-started by the Civil War, when many states cultivated poppies in order to treat not only the excruciating pain of horrific injuries but endemic dysentery. Booth notes that 10 million opium pills and 2 million ounces of opiates in powder or tinctures were distributed by Union forces. Subsequently, vast numbers of veterans became addicted — the condition became known as “Soldier’s Disease” — and their high became more intense with the developments of morphine and the hypodermic needle. They were joined by millions of wives, sisters, and mothers who, consumed by postwar grief, sought refuge in the obliviating joy that opiates offered.

Based on contemporary accounts, it appears that the epidemic of the late 1860s and 1870s was probably more widespread, if far less intense, than today’s — a response to the way in which the war tore up settled ways of life, as industrialization transformed the landscape, and as huge social change generated acute emotional distress. This aspect of the epidemic — as a response to mass social and cultural dislocation — was also clear among the working classes in the earlier part of the 19th century in Britain. As small armies of human beings were lured from their accustomed rural environments, with traditions and seasons and community, and thrown into vast new industrialized cities, the psychic stress gave opium an allure not even alcohol could match. Some historians estimate that as much as 10 percent of a working family’s income in industrializing Britain was spent on opium. By 1870, opium was more available in the United States than tobacco was in 1970. It was as if the shift toward modernity and a wholly different kind of life for humanity necessitated for most working people some kind of relief — some way of getting out of the train while it was still moving.

It is tempting to wonder if, in the future, today’s crisis will be seen as generated from the same kind of trauma, this time in reverse.

If industrialization caused an opium epidemic, deindustrialization is no small part of what’s fueling our opioid surge. It’s telling that the drug has not taken off as intensely among all Americans — especially not among the engaged, multiethnic, urban-dwelling, financially successful inhabitants of the coasts. The poppy has instead found a home in those places left behind — towns and small cities that owed their success to a particular industry, whose civic life was built around a factory or a mine. Unlike in Europe, where cities and towns existed long before industrialization, much of America’s heartland has no remaining preindustrial history, given the destruction of Native American societies. The gutting of that industrial backbone — especially as globalization intensified in a country where market forces are least restrained — has been not just an economic fact but a cultural, even spiritual devastation. The pain was exacerbated by the Great Recession and has barely receded in the years since. And to meet that pain, America’s uniquely market-driven health-care system was more than ready.

The great dream of the medical profession, which has been fascinated by opioids over the centuries, was to create an experience that captured the drug’s miraculous pain relief but somehow managed to eliminate its intoxicating hook. The attempt to refine opium into a pain reliever without addictive properties produced morphine and later heroin — each generated by perfectly legal pharmaceutical and medical specialists for the most enlightened of reasons. (The word heroin was coined from the German word Heroisch, meaning “heroic,” by the drug company Bayer.) In the mid-1990s, OxyContin emerged as the latest innovation: A slow timed release would prevent sudden highs or lows, which, researchers hoped, would remove craving and thereby addiction. Relying on a single study based on a mere 38 subjects, scientists concluded that the vast majority of hospital inpatients who underwent pain treatment with strong opioids did not go on to develop an addiction, spurring the drug to be administered more widely.

This reassuring research coincided with a social and cultural revolution in medicine: In the wake of the AIDS epidemic, patients were becoming much more assertive in managing their own treatment — and those suffering from debilitating pain began to demand the relief that the new opioids promised. The industry moved quickly to cash in on the opportunity: aggressively marketing the new drugs to doctors via sales reps, coupons, and countless luxurious conferences, while waging innovative video campaigns designed to be played in doctors’ waiting rooms. As Sam Quinones explains in his indispensable account of the epidemic, Dreamland, all this happened at the same time that doctors were being pressured to become much more efficient under the new regime of “managed care.” It was a fateful combination: Patients began to come into doctors’ offices demanding pain relief, and doctors needed to process patients faster. A “pain” diagnosis was often the most difficult and time-consuming to resolve, so it became far easier just to write a quick prescription to abolish the discomfort rather than attempt to isolate its cause. The more expensive and laborious methods for treating pain — physical and psychological therapy — were abandoned almost overnight in favor of the magic pills.

A huge new supply and a burgeoning demand thereby created a massive new population of opioid users. Getting your opioid fix no longer meant a visit to a terrifying shooting alley in a ravaged city; now it just required a legitimate prescription and a bottle of pills that looked as bland as a statin or an SSRI. But as time went on, doctors and scientists began to realize that they were indeed creating addicts. Much of the initial, hopeful research had been taken from patients who had undergone opioid treatment as inpatients, under strict supervision. No one had examined the addictive potential of opioids for outpatients, handed bottles and bottles of pills, in doses that could be easily abused. Doctors and scientists also missed something only recently revealed about OxyContin itself: Its effects actually declined after a few hours, not 12 — thus subjecting most patients to daily highs and lows and the increased craving this created. Patients whose pain hadn’t gone away entirely were kept on opioids for longer periods of time and at higher dosages. And OxyContin had not removed the agonies of withdrawal: Someone on painkillers for three months would often find, as her prescription ran out, that she started vomiting or was convulsed with fever. The quickest and simplest solution was a return to the doctor.

Add to this the federal government’s move in the mid-1980s to replace welfare payments for the poor with disability benefits — which covered opioids for pain — and unscrupulous doctors, often in poorer areas, found a way to make a literal killing from shady pill mills. So did many patients. A Medicaid co-pay of $3 for a bottle of pills, as Quinones discovered, could yield $10,000 on the streets — an economic arbitrage that enticed countless middle-class Americans to become drug dealers. One study has found that 75 percent of those addicted to opioids in the United States began with prescription painkillers given to them by a friend, family member, or dealer. As a result, the social and cultural profile of opioid users shifted as well: The old stereotype of a heroin junkie — a dropout or a hippie or a Vietnam vet — disappeared in the younger generation, especially in high schools. Football players were given opioids to mask injuries and keep them on the field; they shared them with cheerleaders and other popular peers; and their elevated social status rebranded the addiction. Now opiates came wrapped in the bodies and minds of some of the most promising, physically fit, and capable young men and women of their generation. Courtesy of their doctors and coaches.

It’s hard to convey the sheer magnitude of what happened. Between 2007 and 2012, for example, 780 million hydrocodone and oxycodone pills were delivered to West Virginia, a state with a mere 1.8 million residents. In one town, population 2,900, more than 20 million opioid prescriptions were processed in the past decade. Nationwide, between 1999 and 2011, oxycodone prescriptions increased sixfold. National per capita consumption of oxycodone went from around 10 milligrams in 1995 to almost 250 milligrams by 2012.

The quantum leap in opioid use arrived by stealth. Most previous drug epidemics were accompanied by waves of crime and violence, which prompted others, outside the drug circles, to take notice and action. But the opioid scourge was accompanied, during its first decade, by a record drop in both. Drug users were not out on the streets causing mayhem or havoc. They were inside, mostly alone, and deadly quiet. There were no crack houses to raid or gangs to monitor. Overdose deaths began to climb, but they were often obscured by a variety of dry terms used in coroners’ reports to hide what was really happening. When the cause of death was inescapable — young corpses discovered in bedrooms or fast-food restrooms — it was also, frequently, too shameful to share. Parents of dead teenagers were unlikely to advertise their agony.

In time, of course, doctors realized the scale of their error. Between 2010 and 2015, opioid prescriptions declined by 18 percent. But if it was a huge, well-intended mistake to create this army of addicts, it was an even bigger one to cut them off from their supply. That is when the addicted were forced to turn to black-market pills and street heroin. Here again, the illegal supply channel broke with previous patterns. It was no longer controlled by the established cartels in the big cities that had historically been the main source of narcotics. This time, the heroin — particularly cheap, black-tar heroin from Mexico — came from small drug-dealing operations that avoided major urban areas, instead following the trail of methadone clinics and pill mills into the American heartland.

Their innovation, Quinones discovered, was to pay the dealers a flat salary, rather than a cut from the heroin itself. This removed the incentives to weaken the product, by cutting it with baking soda or other additives, and so made the new drug much more predictable in its power and reliable in its dosage. And rather than setting up a central location to sell the drugs — like a conventional shooting gallery or crack house — the new heroin marketers delivered it by car. Outside methadone clinics or pill mills, they handed out cards bearing only a telephone number. Call them and they would arrange to meet you near your house, in a suburban parking lot. They were routinely polite and punctual.

Buying heroin became as easy in the suburbs and rural areas as buying weed in the cities. No violence, low risk, familiar surroundings: an entire system specifically designed to provide a clean-cut, friendly, middle-class high. America was returning to the norm of the 19th century, when opiates were a routine medicine, but it was consuming compounds far more potent, addictive, and deadly than any 19th-century tincture enthusiast could have imagined. The country resembled someone who had once been accustomed to opium, who had spent a long time in recovery, whose tolerance for the drug had collapsed, and who was then offered a hit of the most powerful new variety.

The iron law of prohibition, as first stipulated by activist Richard Cowan in 1986, is that the more intense the crackdown, “the more potent the drugs will become.” In other words, the harder the enforcement, the harder the drugs. The legal risks associated with manufacturing and transporting a drug increase exponentially under prohibition, which pushes the cost of supplying the drug higher, which incentivizes traffickers to minimize the size of the product, which leads to innovations in higher potency. That’s why, during the prohibition of alcohol, much of the production and trafficking was in hard liquor, not beer or wine; why amphetamines evolved into crystal meth; why today’s cannabis is much more potent than in the late-20th century. Heroin, rather than old-fashioned opium, became the opioid of the streets.

Then came fentanyl, a massively concentrated opioid that delivers up to 50 times the strength of heroin. Developed in 1959, it is now one of the most widely used opioids in global medicine, its miraculous pain relief delivered through transdermal patches, or lozenges, that have revolutionized surgery and recovery and helped save countless lives. But in its raw form, it is one of the most dangerous drugs ever created by human beings. A recent shipment of fentanyl seized in New Jersey fit into the trunk of a single car yet contained enough poison to wipe out the entire population of New Jersey and New York City combined. That’s more potential death than a dirty bomb or a small nuke. That’s also what makes it a dream for traffickers. A kilo of heroin can yield $500,000; a kilo of fentanyl is worth as much as $1.2 million.

The problem with fentanyl, as it pertains to traffickers, is that it is close to impossible to dose correctly. To be injected at all, fentanyl’s microscopic form requires it to be cut with various other substances, and that cutting is playing with fire. Just the equivalent of a few grains of salt can send you into sudden paroxysms of heaven; a few more grains will kill you. It is obviously not in the interests of drug dealers to kill their entire customer base, but keeping most of their clients alive appears beyond their skill. The way heroin kills you is simple: The drug dramatically slows the respiratory system, suffocating users as they drift to sleep. Increase the potency by a factor of 50 and it is no surprise that you can die from ingesting just a half a milligram of the stuff.

Fentanyl comes from labs in China; you can find it, if you try, on the dark web. It’s so small in size and so valuable that it’s close to impossible to prevent it coming into the country. Last year, 500 million packages of all kinds entered the United States through the regular mail — making them virtually impossible to monitor with the Postal Service’s current technology. And so, over the past few years, the impact of opioids has gone from mass intoxication to mass death. In the last heroin epidemic, as Vietnam vets brought the addiction back home, the overdose rate was 1.5 per 10,000 Americans. Now, it’s 10.5. Three years ago in New Jersey, 2 percent of all seized heroin contained fentanyl. Today, it’s a third. Since 2013, overdose deaths from fentanyl and other synthetic opioids have increased sixfold, outstripping those from every other drug.

If the war on drugs is seen as a century-long game of chess between the law and the drugs, it seems pretty obvious that fentanyl, by massively concentrating the most pleasurable substance ever known to mankind, is checkmate.

Watching as this catastrophe unfolded these past few years, I began to notice how closely it resembles the last epidemic that dramatically reduced life-spans in America: AIDS. It took a while for anyone to really notice what was happening there, too. AIDS occurred in a population that was often hidden and therefore distant from the cultural elite (or closeted within it). To everyone else, the deaths were abstract, and relatively tolerable, especially as they were associated with an activity most people disapproved of. By the time the epidemic was exposed and understood, so much damage had been done that tens of thousands of deaths were already inevitable.

Today, once more, the cultural and political elites find it possible to ignore the scale of the crisis because it is so often invisible in their — our — own lives. The polarized nature of our society only makes this worse: A plague that is killing the other tribe is easier to look away from. Occasionally, members of the elite discover their own children with the disease, and it suddenly becomes more urgent. A celebrity death — Rock Hudson in 1985, Prince in 2016 — begins to break down some of the denial. Those within the vortex of death get radicalized by the failure of government to tackle the problem. The dying gay men who joined ACT UP in the 1980s share one thing with the opioid-ridden communities who voted for Donald Trump in unexpected numbers: a desperate sense of powerlessness, of living through a plague that others are choosing not to see.

At some point, the sheer numbers of the dead become unmissable. With AIDS, the government, along with pharmaceutical companies, eventually developed a plan of action: prevention, education, and research for a viable treatment and cure. Some of this is happening with opioids. The widespread distribution of Narcan sprays — which contain the antidote naloxone — has already saved countless lives. The use of alternative, less-dangerous opioid drugs such as methadone and buprenorphine to wean people off heroin or cushion them through withdrawal has helped. Some harm-reduction centers have established needle-exchange programs. But none of this comes close to stopping the current onslaught. With HIV and AIDS, after all, there was a clear scientific goal: to find drugs that would prevent HIV from replicating. With opioid addiction, there is no such potential cure in the foreseeable future. When we see the toll from opioids exceed that of peak AIDS deaths, it’s important to remember that after that peak came a sudden decline. After the latest fentanyl peak, no such decline looks probable. On the contrary, the deaths continue to mount.

Over time, AIDS worked its way through the political system.

More than anything else, it destroyed the closet and massively accelerated our culture’s acceptance of the dignity and humanity of homosexuals. Marriage equality and open military service were the fruits of this transformation. But with the opioid crisis, our politics has remained curiously unmoved. The Trump administration, despite overwhelming support from many of the communities most afflicted, hasn’t appointed anyone with sufficient clout and expertise to corral the federal government to respond adequately.

The critical Office of National Drug Control Policy has spent a year without a permanent director. Its budget is slated to be slashed by 95 percent, and until a few weeks ago, its deputy chief of staff was a 24-year-old former campaign intern. Kellyanne Conway — Trump’s “opioid czar” — has no expertise in government, let alone in drug control. Although Trump plans to increase spending on treating addiction, the overall emphasis is on an even more intense form of prohibition, plus an advertising campaign. Attorney General Jeff Sessions even recently opined that he believes marijuana is really the key gateway to heroin — a view so detached from reality it beggars belief. It seems clear that in the future, Trump’s record on opioids will be as tainted as Reagan’s was on AIDS. But the human toll could be even higher.

One of the few proven ways to reduce overdose deaths is to establish supervised injection sites that eventually wean users off the hard stuff while steering them into counseling, safe housing, and job training.

After the first injection site in North America opened in Vancouver, deaths from heroin overdoses plunged by 35 percent. In Switzerland, where such sites operate nationwide, overdose deaths have been cut in half. By treating the addicted as human beings with dignity rather than as losers and criminals who have ostracized themselves, these programs have coaxed many away from the cliff face of extinction toward a more productive life.

But for such success to be replicated in the United States, we would have to contemplate actually providing heroin to addicts in some cases, and we’d have to shift much of the current spending on prohibition, criminalization, and incarceration into a huge program of opioid rehabilitation. We would, in short, have to end the war on drugs. We are nowhere near prepared to do that. And in the meantime, the comparison to act up is exceedingly depressing, as the only politics that opioids appear to generate is nihilistic and self-defeating. The drug itself saps initiative and generates social withdrawal. A few small activist groups have sprung up, but it is hardly a national movement of any heft or urgency.

And so we wait to see what amount of death will be tolerable in America as the price of retaining prohibition. Is it 100,000 deaths a year? More? At what point does a medical emergency actually provoke a government response that takes mass death seriously? Imagine a terror attack that killed over 40,000 people. Imagine a new virus that threatened to kill 52,000 Americans this year. Wouldn’t any government make it the top priority before any other?

In some ways, the spread of fentanyl — now beginning to infiltrate cocaine, fake Adderall, and meth, which is also seeing a spike in use — might best be thought of as a mass poisoning. It has infected often nonfatal drugs and turned them into instant killers. Think back to the poison discovered in a handful of tainted Tylenol pills in 1982. Every bottle of Tylenol in America was immediately recalled; in Chicago, police went into neighborhoods with loudspeakers to warn residents of the danger. That was in response to a scare that killed, in total, seven people. In 2016, 20,000 people died from overdosing on synthetic opioids, a form of poison in the illicit drug market. Some lives, it would appear, are several degrees of magnitude more valuable than others. Some lives are not worth saving at all.

One of the more vivid images that Americans have of drug abuse is of a rat in a cage, tapping a cocaine-infused water bottle again and again until the rodent expires. Years later, as recounted in Johann Hari’s epic history of the drug war, Chasing the Scream, a curious scientist replicated the experiment. But this time he added a control group. In one cage sat a rat and a water dispenser serving diluted morphine. In another cage, with another rat and an identical dispenser, he added something else: wheels to run in, colored balls to play with, lots of food to eat, and other rats for the junkie rodent to play or have sex with. Call it rat park. And the rats in rat park consumed just one-fifth of the morphine water of the rat in the cage. One reason for pathological addiction, it turns out, is the environment. If you were trapped in solitary confinement, with only morphine to pass the time, you’d die of your addiction pretty swiftly too. Take away the stimulus of community and all the oxytocin it naturally generates, and an artificial variety of the substance becomes much more compelling.

One way of thinking of postindustrial America is to imagine it as a former rat park, slowly converting into a rat cage. Market capitalism and revolutionary technology in the past couple of decades have transformed our economic and cultural reality, most intensely for those without college degrees. The dignity that many working-class men retained by providing for their families through physical labor has been greatly reduced by automation. Stable family life has collapsed, and the number of children without two parents in the home has risen among the white working and middle classes. The internet has ravaged local retail stores, flattening the uniqueness of many communities. Smartphones have eviscerated those moments of oxytocin-friendly actual human interaction. Meaning — once effortlessly provided by a more unified and often religious culture shared, at least nominally, by others — is harder to find, and the proportion of Americans who identify as “nones,” with no religious affiliation, has risen to record levels. Even as we near peak employment and record-high median household income, a sense of permanent economic insecurity and spiritual emptiness has become widespread. Some of that emptiness was once assuaged by a constantly rising standard of living, generation to generation.

But that has now evaporated for most Americans.

New Hampshire, Ohio, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania have overtaken the big cities in heroin use and abuse, and rural addiction has spread swiftly to the suburbs. Now, in the latest twist, opioids have reemerged in that other, more familiar place without hope: the black inner city, where overdose deaths among African-Americans, mostly from fentanyl, are suddenly soaring. To make matters worse, political and cultural tribalism has deeply weakened the glue of a unifying patriotism to give a broader meaning to people’s lives — large numbers of whites and blacks both feel like strangers in their own land. Mass immigration has, for many whites, intensified the sense of cultural abandonment. Somewhere increasingly feels like nowhere.

It’s been several decades since Daniel Bell wrote The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism, but his insights have proven prescient. Ever-more-powerful market forces actually undermine the foundations of social stability, wreaking havoc on tradition, religion, and robust civil associations, destroying what conservatives value the most. They create a less human world. They make us less happy. They generate pain.

This was always a worry about the American experiment in capitalist liberal democracy. The pace of change, the ethos of individualism, the relentless dehumanization that capitalism abets, the constant moving and disruption, combined with a relatively small government and the absence of official religion, risked the construction of an overly atomized society, where everyone has to create his or her own meaning, and everyone feels alone. The American project always left an empty center of collective meaning, but for a long time Americans filled it with their own extraordinary work ethic, an unprecedented web of associations and clubs and communal or ethnic ties far surpassing Europe’s, and such a plethora of religious options that almost no one was left without a purpose or some kind of easily available meaning to their lives. Tocqueville marveled at this American exceptionalism as the key to democratic success, but he worried that it might not endure forever.

And it hasn’t. What has happened in the past few decades is an accelerated waning of all these traditional American supports for a meaningful, collective life, and their replacement with various forms of cheap distraction. Addiction — to work, to food, to phones, to TV, to video games, to porn, to news, and to drugs — is all around us. The core habit of bourgeois life — deferred gratification — has lost its grip on the American soul. We seek the instant, easy highs, and it’s hard not to see this as the broader context for the opioid wave. This was not originally a conscious choice for most of those caught up in it: Most were introduced to the poppy’s joys by their own family members and friends, the last link in a chain that included the medical establishment and began with the pharmaceutical companies. It may be best to think of this wave therefore not as a function of miserable people turning to drugs en masse but of people who didn’t realize how miserable they were until they found out what life without misery could be. To return to their previous lives became unthinkable. For so many, it still is.

If Marx posited that religion is the opiate of the people, then we have reached a new, more clarifying moment in the history of the West: Opiates are now the religion of the people. A verse by the poet William Brewer sums up this new world:

Where once was faith,

there are sirens: red lights spinning

door to door, a record twenty-four

in one day, all the bodies

at the morgue filled with light.

It is easy to dismiss or pity those trapped or dead for whom opiates have filled this emptiness. But it’s not quite so easy for the tens of millions of us on antidepressants, or Xanax, or some benzo-drug to keep less acute anxieties at bay. In the same period that opioids have spread like wildfire, so has the use of cannabis — another downer nowhere near as strong as opiates but suddenly popular among many who are the success stories of our times. Is it any wonder that something more powerful is used by the failures? There’s a passage in one of Brewer’s poems that tears at me all the time. It’s about an opioid-addicted father and his son. The father tells us:

Times my simple son will shake me to,

syringe still hanging like a feather from my arm.

What are you always doing, he asks.

Flying, I say. Show me how, he begs.

And finally, I do. You’d think

the sun had gotten lost inside his head,

the way he smiled.

To see this epidemic as simply a pharmaceutical or chemically addictive problem is to miss something: the despair that currently makes so many want to fly away. Opioids are just one of the ways Americans are trying to cope with an inhuman new world where everything is flat, where communication is virtual, and where those core elements of human happiness — faith, family, community — seem to elude so many. Until we resolve these deeper social, cultural, and psychological problems, until we discover a new meaning or reimagine our old religion or reinvent our way of life, the poppy will flourish.

We have seen this story before — in America and elsewhere.

The allure of opiates’ joys are filling a hole in the human heart and soul today as they have since the dawn of civilization. But this time, the drugs are not merely laced with danger and addiction. In a way never experienced by humanity before, the pharmaceutically sophisticated and ever more intense bastard children of the sturdy little flower bring mass death in their wake. This time, they are agents of an eternal and enveloping darkness. And there is a long, long path ahead, and many more bodies to count, before we will see any light.

*This article appears in the February 19, 2018, issue of New York Magazine.