As interactions between humans and artificial intelligence (AI) accelerate at a rapid pace, researchers from numerous disciplines are beginning to investigate the societal implications — among them Penn State Associate Professor of Psychology and Sherwin Early Career Professor in the Rock Ethics Institute C. Daryl Cameron.

Cameron is currently integrating AI research into his role as director of Penn State’s Consortium on Moral Decision-Making, an interdisciplinary hub of scholars focused on moral and ethical decision making that’s co-funded by the Social Science Research Institute (SSRI), Rock Ethics Institute and College of the Liberal Arts, with additional funding from the McCourtney Institute for Democracy and the Department of Philosophy.

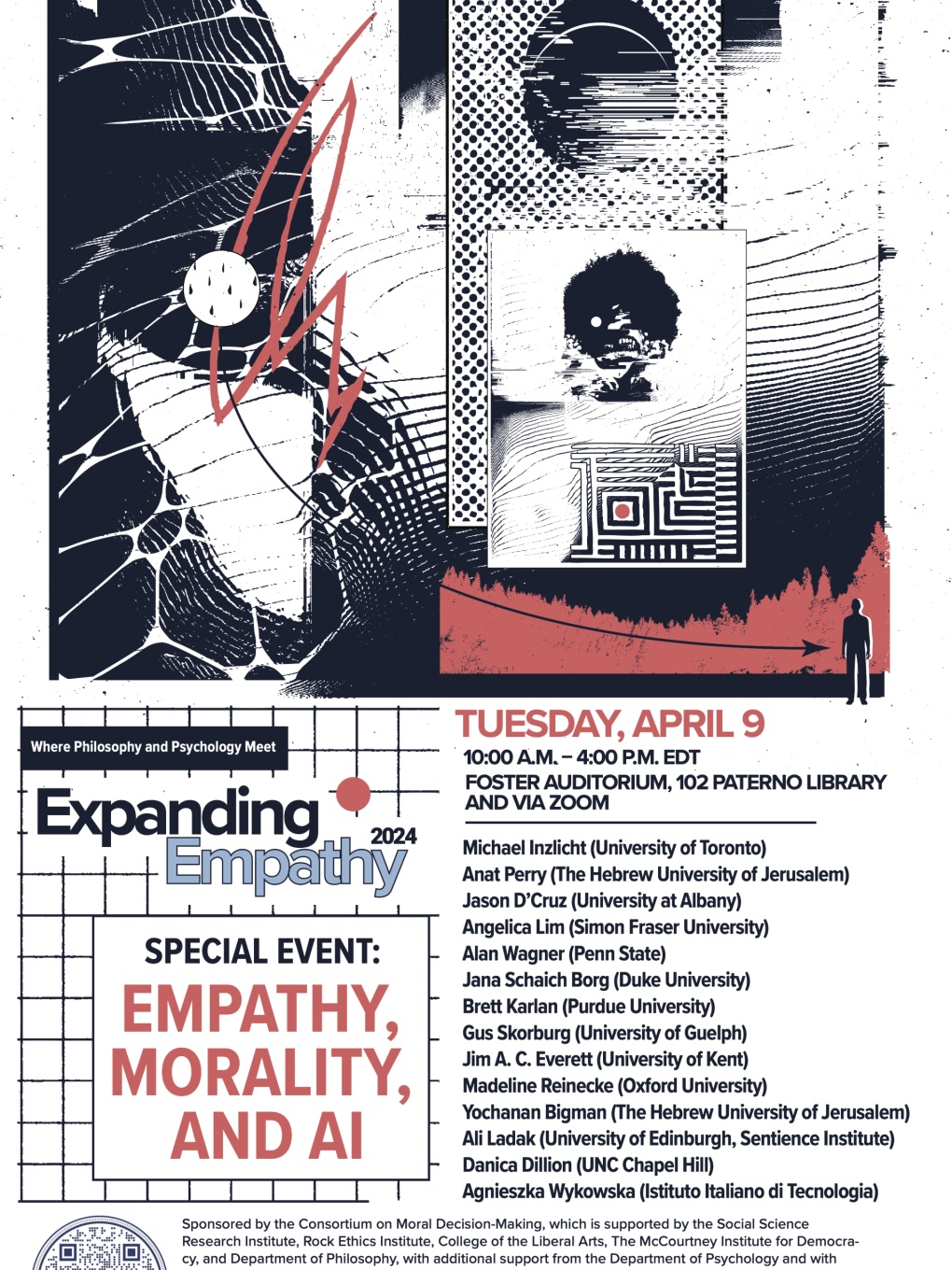

On Tuesday, April 9, the consortium will host the “AI, Empathy, and Morality” conference in partnership with the Center for Socially Responsible Artificial Intelligence and University Libraries. Taking place from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. in Foster Auditorium, 102 Paterno Library, and part of the consortium’s Expanding Empathy series, the event will feature presenters from the United States, England, Scotland, Canada, Italy and Israel. For more information, or to register to attend in person or via Zoom, click here.

Meanwhile, Cameron recently collaborated with three other researchers on the article, “In Praise of Empathic AI,” which was published in the journal Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

The article examines the pros and cons that come with people’s response to AI’s ability to replicate empathy, and highlights AI’s “unique ability to simulate empathy without the same biases that afflict humans.”

AI chatbots like ChatGPT continue to grow both in popularity and in their ability to demonstrate empathy – such as the ability to recognize someone’s emotions, see things from their perspective, and respond with care and compassion – and other “human” qualities. These “perceived expressions of empathy” can leave people feeling that someone cares for them, even if it’s coming from an AI, noted Cameron and his co-authors, Michael Inzlicht from the University of Toronto; Jason D’Cruz from University at Albany SUNY; and Paul Bloom from the University of Toronto. Inzlicht and D’Cruz are both slated to present at the April 9 conference.

Cameron, who also leads Penn State’s Empathy and Moral Psychology Lab, recently shared some of his thoughts on the AI-empathy dynamic.

Q: What inspired you and your fellow researchers to write the journal article?

Cameron: It’s easy to fall into these conversational modes with AI — it does feel like you’re asking something of it and it gives you a response, as if you’re having an actual human interaction. Given the social and ethical questions involved, we thought this would be a good idea for a short thought paper. Some of the responses we got were intriguing, and it raised a lot of fascinating questions.

Q: You and your co-authors cite a recent study where ChatGPT was perceived by licensed health care providers to provide better quality diagnoses and demonstrate superior bedside manner than actual physicians to patients posting medical symptoms to a discussion board on the website Reddit. And in your own encounters with it, you were impressed with AI’s simulated empathy, including the way it conveyed sorrow and joy. But you also note that it always stated it was incapable of having actual human feelings. Why is that disclosure critical to the interaction?

Cameron: AI can give us enough of what we want from an empathetic response. It lacks the essence of real empathy, but if you’re treating it as real empathy, you’re making a mistake. We can think about it from the perspective of what the perceiver thinks: ‘What is it doing for them?’ Rather than wholly dismiss AI empathy as something not real, why not look at the social needs people might get from receiving these responses and then work with that.

Q: You and your co-authors suggest people can feel cared for by AI chatbots and therapists, comparing it to the parasocial — one-sided — relationships people form with fictional TV characters or celebrities like pop superstar Taylor Swift. What do you make of that?

Cameron: I think that people can get a lot out of many different kinds of interactions, even if there isn’t someone who is truly responding back on the other end. We form connections to the characters in narratives like books or films, with sports teams and so on, and those connections can satisfy many of our social needs for attachment and belonging. If you can somewhat satisfy some of those social affiliation needs through interaction with chatbots — even if you know they are not really empathizing with you on some level — who is to judge that the 'empathy' in that case doesn’t matter to you? My first-year graduate student Joshua Wenger and I are working together on some new studies on how we respond to empathy and moral disagreements received from AI chatbots.

Q: While human empathy is obviously imperfect, you found that AI’s simulated version is tireless, and appears fully capable of empathizing equally with people no matter their ethnic, racial or religious background. But as you and your co-authors point out, there are several potential risks to consider, such as people preferring AI’s simulated empathy to the real thing, or deciding it’s easier to “outsource” their empathy to AI, in turn diminishing their own ability to empathize. How should these potential risks be dealt with?

Cameron: As we note in the article, it remains to be seen if AI is capable of expressing empathy with the 'moral discernment' required for it to be beneficial. For me, one of the most interesting questions is, even if you acknowledge that it’s a simulation and not fully real, can you use it as a tool to practice empathy? That’s the kind of thing that can have a net positive. We think this is a conversation starter meant to be the opening of a question. Rather than entirely dismiss it, we should explore some potential positives, while admitting there’s still a lot more work to be done on it.

Q: What are some of your hopes on the subject moving forward?

Cameron: Our short little think piece was meant to be an interdisciplinary appetizer of sorts. We want to keep exploring the subject because we don’t think there’s a one-size-fits-all answer. No one study can reveal that. Some might say AI is less valuable than human empathy, but some others might not. And we want to use this space to think about our own capacity for empathy. I’ve enjoyed having the opportunity to chat and do work with my Rock Ethics colleague Alan Wagner about these topics for the past several years, including on whether and how we feel empathy differently for robots and humans — does whether we feel empathy for the destruction of a humanoid robot like Pepper, whether we feel callous or sympathetic — tell us something about how we might respond to the pain of humans or non-human animals? Or does it tell us that we know the boundaries of sentience, and does the question of empathy for experiences make sense in that context for a target that doesn’t have consciousness?

This is one area where I’m especially excited about the conference. We’ll have people with a variety of perspectives talking on whether perceived empathy from AI is useful or not, including scientists Michael Inzlicht, Anat Perry and Jana Schaich Borg. Some are more positive about it, and some think AI empathy will never really be empathy in the way that’s important for our moral development. We’ll also have some scholars who are asking questions about what it takes to trust in AI — including my colleague Alan Wagner, who works with humanoid robots such as Baxter and Nao — as well as philosophers like Jason D’Cruz and psychologist Yochanan Bigman. We’ll also discuss what we mean when we talk about AI reaching moral 'competence' and how to think about what our benchmarks and uses of it in domains like health care might look like, and some of our guests such as philosophers Gus Skorburg and Brett Karlan, and psychologist Madeline Reinecke, all do interesting work in this space. We’ll have a digital panel of five speakers who are Zoom-ing in from around the world — engineer Angelica Lim, as well as psychologists Agnieszka Wykowska, Jim A. C. Everett, Ali Ladak and Danica Dillion — as well, plus an hour set aside for small group collaboration discussions, and the conference will be live-streamed and then archived for those who cannot attend in person.

We already have nearly 100 people registered based on the last time I checked Zoom, and I’m excited for the continued interdisciplinary developments on this topic. We are planning several writing projects that bring together experts in psychology, philosophy and engineering and look forward to this conference being a catalyst for those conversations.